I’ve decided to do things a bit differently on this blog. I’m not posting stuff often enough. This isn’t helping me to get engagement with other hobbyists. The problem is that I haven’t been posting until I feel I have something to say – which usually means finishing a project – or perhaps exploring an issue in (like mixing paints), which takes quite a long time to write about. But my life, even though I’m retired, has quite a few other things in it other than the hobby. We go on holidays; we have people to stay; I’m chair of governors at the local primary school; I’m on a number of online committees; sometimes I just like to go for a walk or see something with my wife; and there’s the garden. The hobby has to squeeze into this agenda, and often involves a number of parallel activities which take time to resolve. There a quite long stretches when I don’t finish something, or don’t feel I have time to write a long blog piece.

But often people just like to know what you are up to. My plan is to do regular hobby updates – at least one a month. These may not take long to write (though this one is quite long) – but should be enough for any followers to have an idea about what I’m doing. This is the first and I’ll cover what I have up to since the last post, in July, following my rather unsuccessful game for the Battle of Medenine (1943) in June, featuring innovative game mechanisms.

Games

I have played just one miniatures game in the period – an Arab-Israeli scenario from the 1967 war, using Cold War Commander. This was with my regular London group of players (mainly from my ex-club of South London Warlords). This was entertaining but a bit one-sided (to the Israelis) – though John, who put the game on, didn’t think it was unrealistic. We used John’s 6mm miniatures – I particularly liked the way he used colour flashes on the back of the base to denote unit ID, without the use of labels. The rules I was a bit less impressed with. I had used the very similar Blitzkrieg Commander before, with a similar reaction.

After this the London group has met a couple of times, but playing a board game – Here I Stand – representing the Reformation in Europe. We played it quite a bit a few years ago – it’s an excellent game but no miniatures! We have one more round to go, in November.

Meanwhile my commitments conspired against my regular club’s days. I haven’t been able to play there since March. Thankfully I’ll be back on 2 November. We haven’t decided on a game yet.

Projects

The Medinine game was a bit of a downer for me. I am a long way from having a decent system for brigade level games in 1943, after having devoted to quite a bit time to trying, and getting things ready. And as for my attempt to create sangars from modelling clay and bits of model railway ballast – I really don’t want to relive that. I decided to give 1943 a long rest. I have plenty else I want to do.

So I have returned to the battle of Custoza in June 1866 in the Third War of Italian Unification (there was also a battle there in the First War in 1848), using home-produced rules. This has been interesting on a number of levels.

Custoza was the main land battle in that war. Taking advantage of Prussia’s attack on Austria, the Italian army attacked the Austrian-occupied province of Venezia. It ran into the Austrian army near Custoza, just southeast of Lake Garda and southwest of Verona. The Austrians were outnumbered but won, forcing the Italians to retreat across the Mincio. However the outcome of the war was soon decided by the Prussians at Koniggratz a few days later, and the Austrians gave up Venezia. The Italians also suffered a naval catastrophe at Lissa.

The battle looks as if it would make a great close-fought and evenly balanced war-game. It is especially interesting because the Austrians used their system of stosstaktik, which proved so disastrous against the Prussians, and is usually written off as being utterly stupid. The Austrian infantry formed into close columns (in divisions of two companies, in contrast with the more typical Napoleonic battalion columns), and went as quickly as possible for the enemy in a bayonet charge. It was no disaster at Custoza, but the Austrians suffered heavily casualties (more than the Italians), so the evidence isn’t conclusive. But it should create an interesting dynamic on the tabletop.

I started this project in 2023 (here and here), and painted up my first batches of figures then, using Pendraken’s 10mm figures. I did one batch each of Italians and Austrians. I also started work on some rules – named Forge of Nations.

Miniatures

I cleared up the considerable mess from the Medenine game from the Studio – the hobby room I have above the garage, nominally shared with my wife, though she has almost never used it. And I then did practically nothing until last week. I picked up the Italians from my last order from Pendraken, featuring all arms and generals. After basing and priming the complete batch, I decided to focus on the infantry – 9 bases of 10 line infantry, and three of 5 bersigelieri. After three sessions these are now ready for finishing (wash/glaze with a dark shade; flocking the bases).

Research

As it happened we went on holiday to Lake Garda a couple of weeks ago. We stayed at Salo on the western shore, but were taken bus to Verona on two occasions. The route crossed the northern edge of the Custoza battle site (from which the Austrians advanced), but it was difficult to see much. The modern motorway was a corridor of ugly modern engineering and the view across country was often obscured. This is the best I could do:

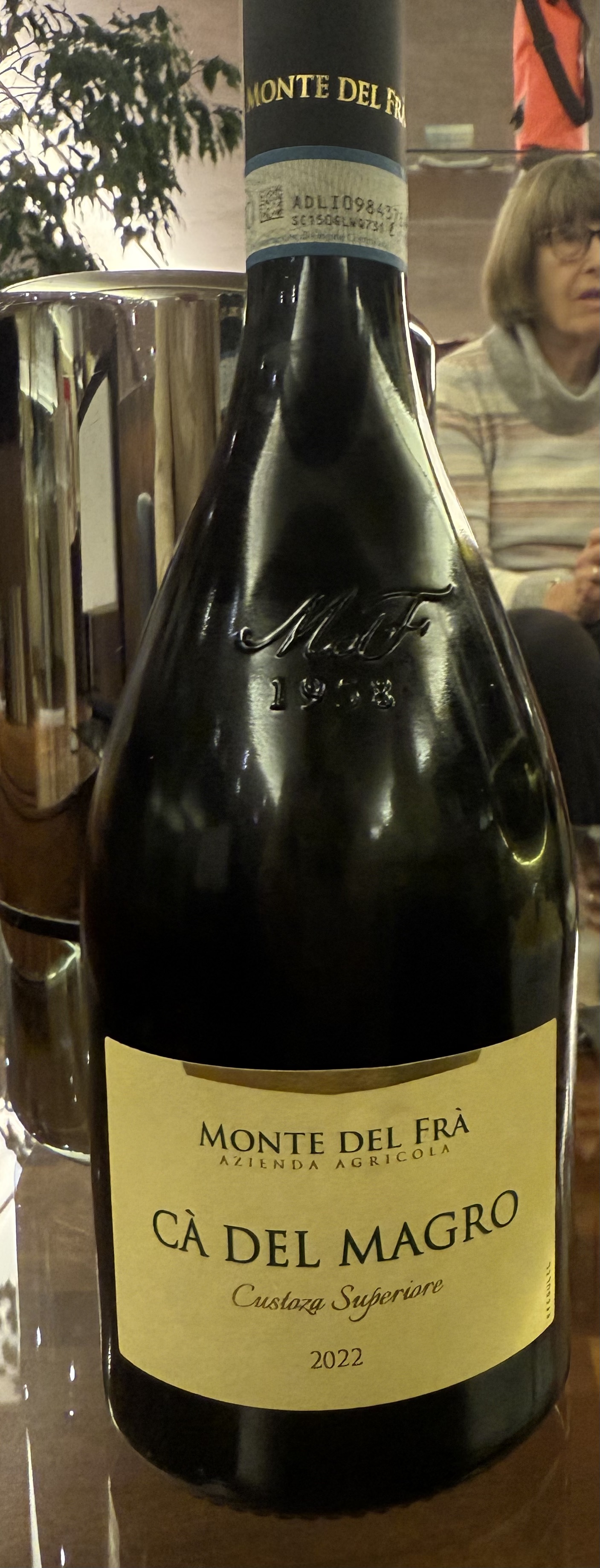

It was interesting to get a general feel for the terrain. The hills dominate the battlefield, but were surprising gentle. This is an area of morainal hills sitting between the mountainous pre-Alps and the flat plain of the Po River. The land is agricultural, and there are a lot of vineyards (the produce of which we sampled, see above), and trees, especially on field boundaries. This limits line of sight, though artillery still played an important role in this battle – doubtless because there were elevated spots with better visibility. It will also be interesting to consider how to present the table visually. The miniatures are relatively boring in appearance (both sides fought in greatcoats, notwithstanding the heat) – so good looking terrain will help. It would be quite nice to take the game to a show but that’s a long shot.

Interestingly, the coach also passed San Martino, at the northern end of the battlefield of Solferino (1859), from the Second War of Unification). I played the Piedmontese (Italians) in a beautiful recreation of this battle hosted by Bruce Weigle at Newbury. The road went right through where my troops were operating. There’s a monument to the battle, which is seen as a glorious Italian victory.

Rules

I have probably spent more time on this activity than anything else. I can do this from the study in the main house, meaning that it’s easier to do short sessions between other activities.

Forge of Nations is designed to cover 1866, including the Austro-Prussian war and 1859. This is but the hors d’oeuvres to the Franco-Prussian war in 1870-71, of course – but that is still a distant prospect.

I had produced a first draft in my first pass at the rules in 2023. This copied quite a bit from my Carolus Rex Great Northern War rules. However, I moved away from the randomised activation of different commands to a more conventional I go/you go system, which is easier to run in multiplayer games. But I wanted to use the card system described in my previous post – with a Move deck to regulate movement, and a Cohesion deck to evaluate combat and rallying.

I think the Move deck is a sound idea, and I want to persist with it. But I have been reflecting on the feedback I received on the Cohesion deck. It replaces dice throws, but comes over as a bit of a black box. Gamers have an intuitive idea about dice odds – and seeing how they land is part of the entertainment. Game design is a careful blend of innovation and conservatism, so I thought I would create a dice system that largely replicates what the cards were meant to do.

My idea is to have one distinctive die to reflect unit quality (D6 for D class, D8 for C, and so on, and then one D6 in place of each card in the old system, which reflect the attacker’s circumstances, such as weapon and range. You add each D6 result to the unit quality die – and see whether it meets a target number – which is adjusted to the unit circumstances. Each fail is a hit. A high score might an Elan result. We’ll see if it works.

Philisophical reflection

It is quite common to design a rules system based on one campaign or period, and then extend it into others. It is interesting to understand how this starting point influences the system. I am hoping to extend my 1866 rules into not just the 1870 war, but back into the Napoleonic and Revolutionary wars, and even into the next version of Carolus Rex, my Great Northern War system.

This is evident from the two different rule systems that I have used that have this battle in scope. One is Bruce Weigle’s 1866 – which is a development of his 1870 system. An interesting feature of this is that it makes extensive use of a “suppression” result for firing. 1870 was probably the first major war where troops often went to ground when fired on – as breech-loading weapons could be fired from the prone position. It is one reason why, in spite of a huge advance in the lethality of firearms, casualties did not escalate (or so I read – casualities in the FPW were still high). This doesn’t seem to have been a feature of the 1866 wars – perhaps the last in history where this applies. The Prussians had breech-loaders, but since their opponents didn’t, they don’t seem to have gone to ground. Still “suppression” could still reflect a hesitancy to move when under fire, and doubtless that is why bruce retained it.

The second system is Chris Pringle’s Bloody Big Battles (BBB). Chris also developed this originally for the FPW, so far as I can tell. But it is based on the Fire & Fury system used for the American Civil War. Going to ground wasn’t a feature of that war either. This is a more abstract system than the 1870 series, with a higher level of scaling (typically a base represents double the number of troops) – so doubtless Chris felt that representing suppression specifically was a needless complication: he has been ruthless in keeping the mechanisms as simple as possible, which is one of the great strengths of the system. However, the European wars of 1859-1871 were not the ACW, even though they are contemporary with it. The weapon systems (for the Prussians in 1866 and both sides in 1870-71) were different and this played a critical role in tactics – but BBB does a careful job of representing this. The use of cavalry was different too – the Europeans clung to the romance of the Napoleonic era, insisting that the charge into close combat was the most important cavalry tactic, and retaining pretty uniforms in many cases, while largely neglecting firearms. The Americans were much more flexible, often deploying cavalry on foot, using firearms – which proved to be the way of the future. BBB retains this approach, with cavalry being very similar to infantry in the way it is represented. Cavalry didn’t play a big role in the European wars, so this doesn’t matter that much. But if you start on the European side of the Atlantic with your system, you would try a bit harder to reflect the possibilities of the grand charge – as the Weigle rules do.

My rules use much the same scaling as BBB, but the base articulation of 1866. Bases move individually, and are not organised into rigid units. Cavalry have a more Napoleonic feel. If I take them into 1870, I will need to reflect suppression in some way, but for now I’m ignoring it.

What BBB and 1866 share, with very different mechanisms, is strong command friction. Command and control is heavily devolved – the direct influence of corps and army commanders is limited – and subject to heavy activation tests. This clearly reflects how things worked in this period – and it is one of the reasons that I find that BBB does not translate so easily into the Napoleonic era – when the action was much more centrally directed, but subject to less friction. This will be interesting to reflect in my rules.

Leave a Reply