In my last post I expressed a some frustration with GDA2 rules, which I have now been using for some time. This moves on to the question of house rules to improve the system. But the rules are widely used and are comprehensive. Messing around with them is not to be done lightly. So I am writing this piece to try and clarify my own thinking.

What I like

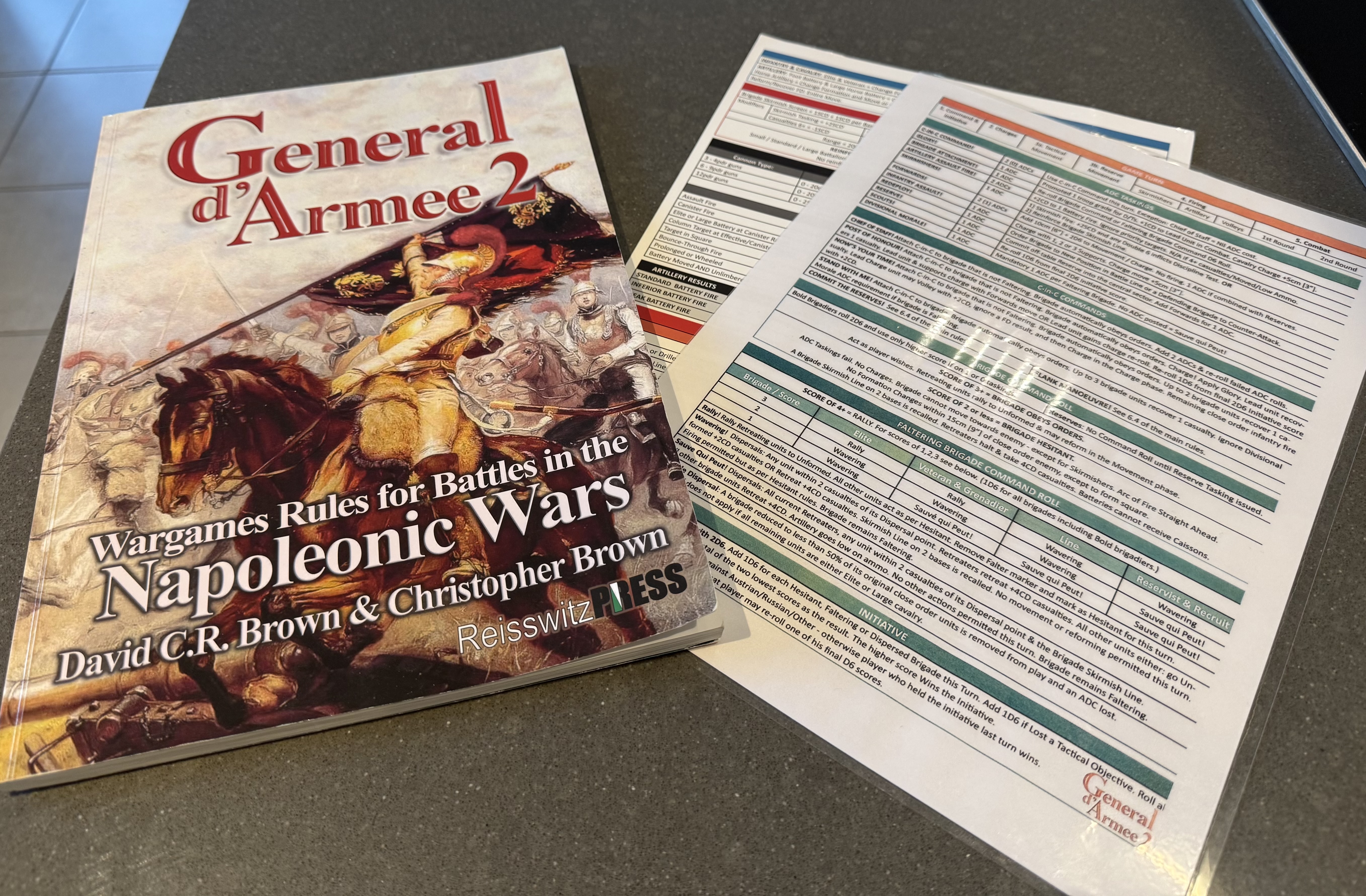

But first we need to get this into some perspective. Why do I like GDA2? I was previously using Sam Mustafa’s Lasalle 2 rules, which are in roughly the same game space. Each side has typically 5-6 brigades of 3 to four infantry battalions or 2-3 cavalry regiments, each typically consisting of four bases, with two bases for an artillery battery. For my 18mm miniatures they can be happily played out on 4ft by 6ft table. Each set has been thoroughly thought through and play-tested by the designers, who both have a deep understanding of Napoleonic warfare.

But the period feel from GDA is so much better than it is for Lasalle. That comes at a considerable cost. Lasalle rules are simpler and so play faster; Sam has put a huge amount of thought into explaining the rules in the simplest possible way, giving them an exemplary clarity. But they are very abstracted and “gamified”. The role of commanders and skirmishers, for example, is abstracted almost out of existence. I, and my fellow gamers, much prefer GDA.

How do the rules achieve this Napoleonic feel? Two things stand out for me. First is the system of “Taskings” and “CinC commands”. These confer specific powers or bonuses to the brigades to which they are awarded. If the rules were written by me I would not use the word “tasking”, which is not a widely used word in English (it means “taskwork” in my dictionary, which is “work done as a task, or by the job” – definitions that don’t really apply here). I would call them “orders” – though that isn’t quite right either. But whatever you call them they do give the feel of a Napoleonic commander directing his troops, without all the problems of doing so more literally on the tabletop. The CinC commands – which are limited to two per game – also reflect the more dramatic interventions that senior commanders sometimes made, and are referred to in battle accounts. The command mechanisms in Lasalle 2 are very clever, and to be fair are better at reflecting move-and-response dynamics, but they feel more like a game than battlefield engagement; they are also harder to adapt to a multi-player format.

A second aspect that works really well is only allowing only one unit from each brigade to conduct a charge in the same move – which may be supported by other units in the brigade. This is the first time that I have seen it in wargames rules, and it really helps give a realistic feel. It stops the common wargame practice of two or more battalion columns bunching up and attacking a battalion deployed in line. This happened to devastating effect in one of my more recent games of Lasalle. It didn’t happen historically – one of those things that look simple on the tabletop that are impossible to accomplish in real life. This changes the dynamics of the battle in ways that give it a more authentic feel.

There are other things. The system has found a way to represent skirmishers that is consequential but not too fiddly – another rare accomplishment. Brigade commanders are represented on the table and have a role. Rules for built-up areas achieve a realistic balance that few systems achieve (though Lasalle 2 isn’t too bad either, unlike its upscale cousin, Blücher).

Minor quibbles

Overall then, it’s an excellent system. I am not tempted to try and design my own system to replace it – which, alas, I often am with rules, though rarely successfully. But there are things I don’t like. Not so much on the detail – I think they are harsh on the firepower of columns, for example – but even there I know that things are the way they are for a reason, based on deep knowledge of the period and experience of game play.

I would be tempted to redo the troop classification system, and change some of the names (e.g. grenadiers ranking below veterans). I would replace the six main categories with four: elite, professional (=veteran & grenadier), conscript (=line) and militia (= reservist & recruit). I would then add a number of special characteristics that could be overlaid (such as “drilled” already in the rules, which I might extend to rapid formation changes as well as firing). I haven’t completely got my head around to the many different sorts of cavalry classification, but I’m sure that could be simplified too. I would be tempted to give 8-gun batteries more resilience (or 6-gun ones less). But I won’t do any of this as it is sure to create more confusion amongst my fellow players, while not really changing anything much.

Another issue I discussed in my previous post is the slow speed of movement of troops outside the immediate combat area. I was a little frustrated by my attempt to move cavalry from one flank to the other in the last game. Of course you might react that it served me right for posting them in the wrong place to start with! A more serious problem is bringing up reserves for an attacking side. The table edge can be a long way from where the troops need to be deployed. These are things that I think are worth fixing with house rules, but that is quite straightforward.

Command system

That leaves two more serious problems: command friction and rules layout. To take the second, the rules are quite detailed but they aren’t laid out very clearly. If you want to refer to a particular rule that you know you’ve read somewhere, it’s often hard to find it in the rulebook (though there is an index which helps enormously). There are four sides of quick-reference sheet on two separate laminated pieces of paper. When trying to find something it is common to pick up the wrong one first, and, especially when a bit tired, it takes much longer to find things there than it should. I am in the process of putting together my own version of the QR sheet, though whether that will work any better remains to be seen. I have already put together my own version of the main rules (but not including the tables in the QR sheets), which is much more compact than the original, which a number of my fellow gamers like, but I still find myself usually going to the main rule book to look things up. All this slows the game down, though as we get more familiar with the rules, this is less of a problem.

Which brings me to the command system, which I discussed at length in my previous post. One issue I didn’t discuss is a problem with rules for bigger battles (of six brigades and more). There is a system for a corps battles, which I’ve read up, but never used. This involves a system of Corps Orders, which are quite detailed and not intuitive. In a big game this year I was asked to command the Austrians at Castaglione – which involved supervising three other players, each with their own GDA divisions. So I read up these rules to be ready – but I was relieved when the games master decided not to use them. It’s an added level complexity that could easily slow the game down. What the games master did instead was to reserve the CinC commands to the army commanders, including the limit of two per game. That worked fine, as it operated within the players’ rules knowledge.

But this points to a curiosity. The typical larger game is played using the divisional game rules as if each side was a large division. That is how the scenarios in the GDA scenario books are set up (though that is based on GDA1 – I don’t know if the Corps game rules are in them). The armies actually consist of two or more divisions. That was the case for the Lützen scenario we played for the Prussians (Ziethen and Klüx)(the French divisions and brigades of the time were large; each brigade was split in two for the scenario, and the infantry all came from the same division). It is true that the typical corps of this period were bigger than this, though. Still, the officer coordinating the battle on each side would surely have been a corps commander, even if there had other troops not on the table to look after as well (Blücher in the case of the Prussian at Lützen). What is more, the CinC commands correspond quite well to the sorts of intervention this corps commander might make (as I pointed out in my previous post). The roles of divisional commander (who would typically have two brigades and a battery) is not represented separately – it is simply integrated with the brigade command roles.

This represents a widespread game design problem. On the wargames table, with the players’ helicopter vision and compressed spaces, representing the full command hierarchy is often impractical. And it is the divisional layer that is usually skipped. But these feature historically important commanders. How to solve?

The Napoleonic command system

I think it is helpful first to reflect on the actual historical roles of generals in this era. Let’s start with the brigade. This was the basic unit of battlefield manoeuvre, consisting usually three or four infantry battalions, or two cavalry regiments. For the Austrians it was bigger: typically two infantry regiments, or six battalions. The Prussians in the later wars operated a more flexible system, with ad hoc groups of battalions being the main battlefield unit, and brigades being the equivalent of divisions in other armies (with 9 battalions and artillery). Earlier in 1813 (including Lützen), Prussian brigades look more typical, with often four battalions. But as reserve and landwehr regiments became incorporated, the brigades got larger.

Brigades would typically be commanded by a Major General (Generalmajor in German) or Général de Brigade for the French (renamed Maréchal de Camp in 1815). Colonels were often brigade leaders too. The Prussians were short of senior officers, so we often find brigade level formations led by Lieutenant- Colonels or even Majors. This is also the case for Hanoverians and other German allied armies in 1815 – doubtless for similar reasons. Note the lack of the rank of Brigadier-General (let alone the 20th century one of Brigadier – a field officer rather than a general). It did exist in the British army at the time, but it was not widely in use in the field, for reasons that I don’t know. “Brigadier” more usually referred to a French NCO. It is interesting that wargamers usually ignore ranks. Of course rank in this era was hardly a guarantee of tactical savvy – but it did convey authority. I think that lower level Prussian tactical leadership was often a bit lacking in 1815 – and the relative lack of seniority of the officers does point that way. This is rarely reflected in wargames rules. Since rank is widely available information in orders of battle I think this is a lost opportunity.

But I digress. The brigade (or perhaps the regiment where brigades comprise six battalions) was the critical tactical element in battlefield organisation, and wargames rules do a good job of reflecting this. A brigade commander would surely spend pretty much his entire time directing his battalions or squadrons. Overall I think GDA does a good job of representing command at this level. It does try to reflect quality of brigade commander (with provision for bold or poor ones) but in the games I have played we tend to ignore this. This is supposed to be determined at random at the start of a battle. The reason I don’t bother is a prosaic one. It’s an extra complication and I don’t have a good way of discreetly labelling it – my labels are typically printed a long way in advance of the game. There’s plenty of random friction in the command system anyway. It would be one way to reflect variations in command quality though – so perhaps Prussians in 1815 would have a high share of “poor” ones. However it would easier to do this by defaulting all an army’s brigade commanders: I haven’t had the courage to do this yet!

Divisions were a major innovation of the Revolutionary-Napoleonic era. Their main role was as a manoeuvre element on campaign, consisting typically of two or three brigades and an artillery battery. It would usually be led by a Lieutenant-General or French Général de Division – but it wasn’t uncommon for the more junior ranks to act up. The Prussians used over-sized brigades instead, consisting, eventually, of three regiments (nine battalions), but typically commanded by a Generalmajor. The battalions were then organised into groups of two to four ad hoc task groups, with the different regiments usually mixed up. These should form the wargames brigades.

A divisional general would typically have only a small staff, but operate in close proximity to his troops. His job was to receive and implement instructions from his superiors, and to communicate back to them. It would also be his job to maintain a wider situational awareness than would be the case for the brigade commanders. They would make direct interventions fairly frequently, often delivering orders in person.

And then we have the corps d’armée, which consisted of a variable number of infantry divisions, together with cavalry support and reserve artillery. These would be commanded by a senior general, in the French case often a Marshal. This was meant to be able to operate as a self-contained army, if need be independently of the main army. There would usually be a substantial staff. The French were the first to adopt this system, but the Austrians, Russians and Prussians had caught on by the mid-war period. Indeed by 1813 their corps commanders were rather more effective than the French ones, in my view. The system never caught on in Wellington’s armies. In the Peninsula he did create what were effectively corps under Hill and Graham, but the main body remained under his direct control. There was a nominal corps system for Wellington’s army in 1815, but this was long way from proper grand-tactical system of other major power armies. On occasion the French dispensed with the corps system too: for example Marmont’s army in 1812, which was organised in a very similar way to Wellington’s.

The problem for GDA is that games are typically bigger than a division but smaller than a corps. The solution is to pretend that the smaller ones are just large divisions, and to have a special corps superstructure for the bigger games. I don’t think this really works, and I want to try and imagine how this might work differently.

GDA command system reimagined

The starting point is that there would be no distinction between divisional and corps games. All games are corps games, though they may not represent a complete corps d’armée, but are played using the Divisional game as a basis. There is a CinC, who might be a corps commander, a divisional officer taking the lead, or even the army commander.

We need to recognise the divisional role. Each side would be divided up into a number of divisions and independent brigades, following the historical order of battle. Divisions would have a divisional commander represented on the table. My inclination is that batteries would not be not treated as part of brigades but as separate parts of a division – unless assigned to support an independent brigade. This needs thinking through, though. Corps reserve batteries may be formed into their own independent brigades of up to two batteries, with a brigade commander.

Start the turn like the Divisional Game. Throw a D6 for each allocated ADC across the whole army. The CinC player then allocates these to divisions and independent brigades, and decides whether to use one of his CinC commands. The Chief of Staff operates at Division level, but all others are brigade interventions.

Players controlling the divisions then throw a D6 for their divisional commanders, unless the division or one its brigades is subject to a CinC command. A score of 3+ means that they may intervene. This means that they are committed to one brigade (or battery), which automatically obeys orders, unless Faltering. This counts as one ADC for Taskings, but no Brigade Attachment tasking is required. In the case of a Faltering brigade, add one to the Command roll die. It replaces the Divisional morale ADC. In this case a Brigade Attachment tasking is allowed (costing a further ADC), and this allows a re-throw.

What is the ADC allocation? I think keep this at the current level, with a maximum of six (dependent on quality). This is clearly more generous than in the current game, as each divisional officer (there are likely to be two) becomes a super-ADC. However, I am proposing to treat batteries as a separate “brigades”. The maximum limit represents the fact that corps commanders could be stretched, and would struggle to manage more complex operations. There is a case for giving the attacker a bonus (or defender a penalty) at the start of the game – perhaps lasting until the move after the first time the defending side wins the initiative.

What about officer quality? There are four grades for CinC, though I hate their names (Blusterer, Commissariat, Campaigner and Incomparable). It is not just personal ability that should reflect this grade: seniority, staff resources and off-table responsibilities (i.e. trying to manage a bigger battle than the one represented on the table) affect this too. Which category should be clear from the historical context. Perhaps rename the categories: Passive; Tentative; Active; Exceptional. I would be inclined to be a bit more generous with the CinC interventions (add one). Or perhaps allow a one ADC interventions to ensure that a particular divisional officer or brigade commander is under control.

For brigades I think that leaders belonging to divisions should be rated as poor (i.e. capable of a single tasking only when left to themselves). Independent brigades would be standard, or bold if the historical context pointed that way. Occasionally they might be poor – perhaps a reluctant attachment from another formation.

Which then leaves divisional leadership. It is doubtless a good idea to represent different levels of effectiveness – and easiest to copy the nomenclature for brigade commanders. Simplest is to vary the score required on the activation die. A poor leader activates on a 4, as they spend more time on dithering and in displacement activity. A bold divisional leader may be activated on a 2. Each of these categories should be quite rare

Which leaves us with the question of initiative. There is no necessity to change the existing rules, which can be based on the number of Hesitant/Faltering brigades. However this is one of the aspects that annoy some gamers. What does it represent? I suppose an army with lots of hesitant brigades is less likely to seize the moment – but there’s an element of that old wargaming vice of double jeopardy there. Isn’t it enough that the brigades are hesitant? Besides some of those hesitant or active brigades may be quietly sitting in the rear or on an inactive flank on standby, not affecting the wider battle. A better idea (one of a number of suggestions from my friend Malc) is to base it on a single die throw based on the CinC rating. So this might be a D10 modified by quality rating (the system used in Age of Eagles, apparently). Or use different types of die depending on quality (a D10 for Active, D8 for Tentative, etc.). This might be modified upwards if the CinC is using Post of Honour, or Scouts and downwards for other CinC interventions (in these cases best to be a die modifier rather than move the quality rerating). Draws preserve the status quo, except Turn 1, which goes to the attacker.

A lot to ponder there. I will let you know how it goes get on!

Leave a Reply