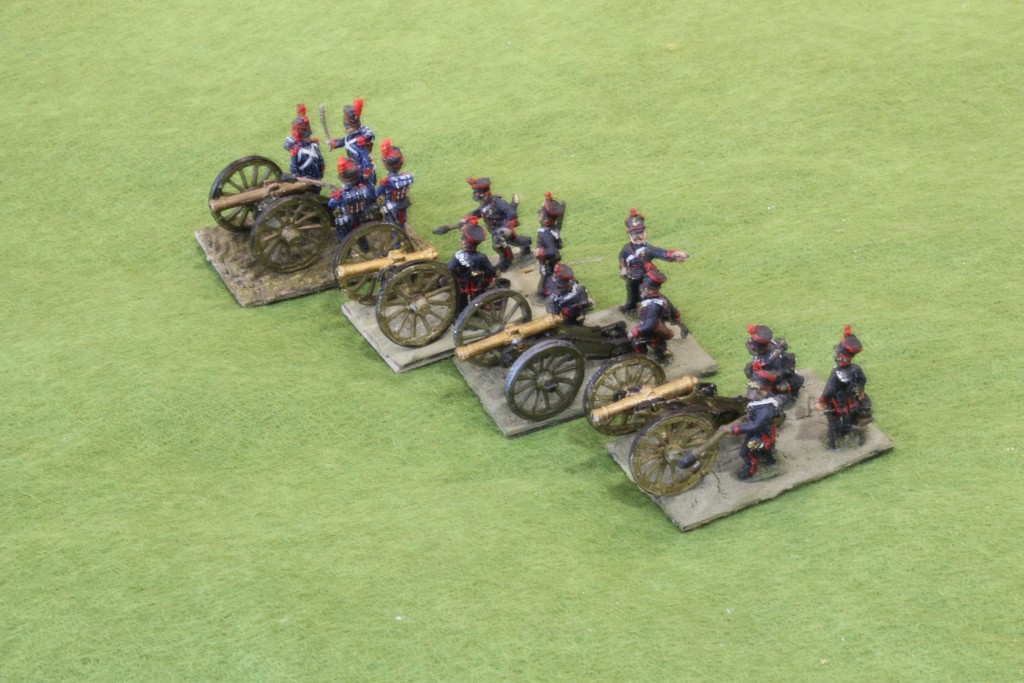

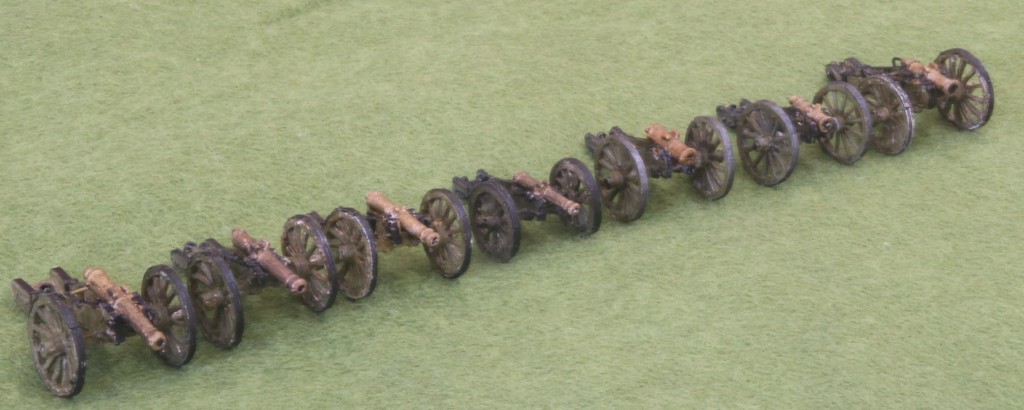

I can now declare the project closed. The final stage was painting up some additional crew figures, correcting the old ones I wanted to re-use, and doing the bases. But this is the article I am linking to TMP, so before describing the finishing touches, I want to summarise what I have done.

I have described the scope in my introductory post. I wanted to provide fresh models for my 15mm French army, whose tin men have grown to more like 18mm over the years – which approximates to 1:100. This is not well catered for in the market, because by the time more accurate information emerged, manufacturers had moved on to other scales, mainly 28mm. My main aim was to produce models for wargames that look approximately right – but there is also an element of building a collection too. Having said that I have neither the patience nor the manual dexterity to produce models of collector standard – the standard that I see so often displayed in TMP. Eye candy this is not.

But I hope it is useful to anybody building French armies in 15/18mm. Many of my models are pulled together from old bits and pieces I have had around for years, and I describe how I did this in my posts. But in this article I will summarise what I recommend to people wanting to use what is out there in the market. This is not based on a comprehensive survey of what is there, but what I know of the more popular makes. They are all Blue Moon and AB, though I have considered others along the way. The headings link to the main articles. So here goes:

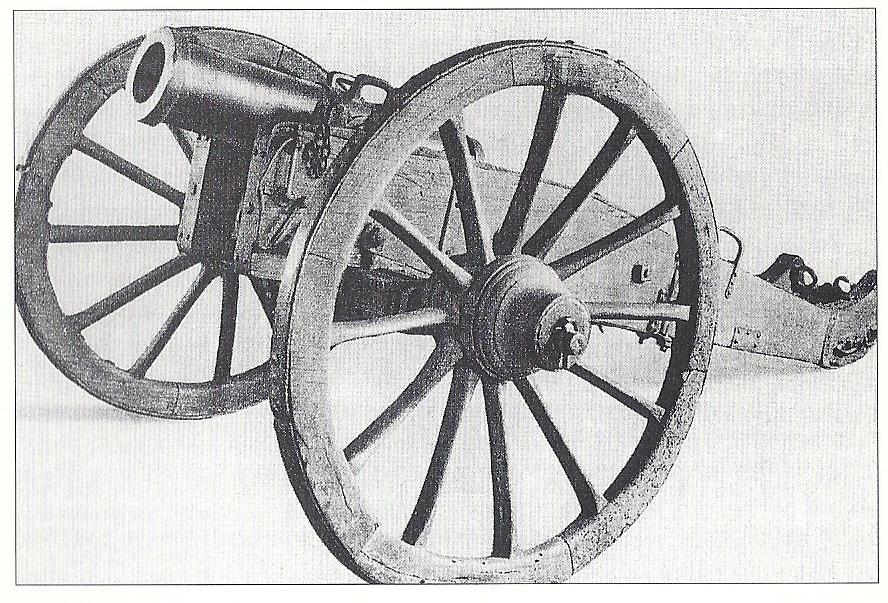

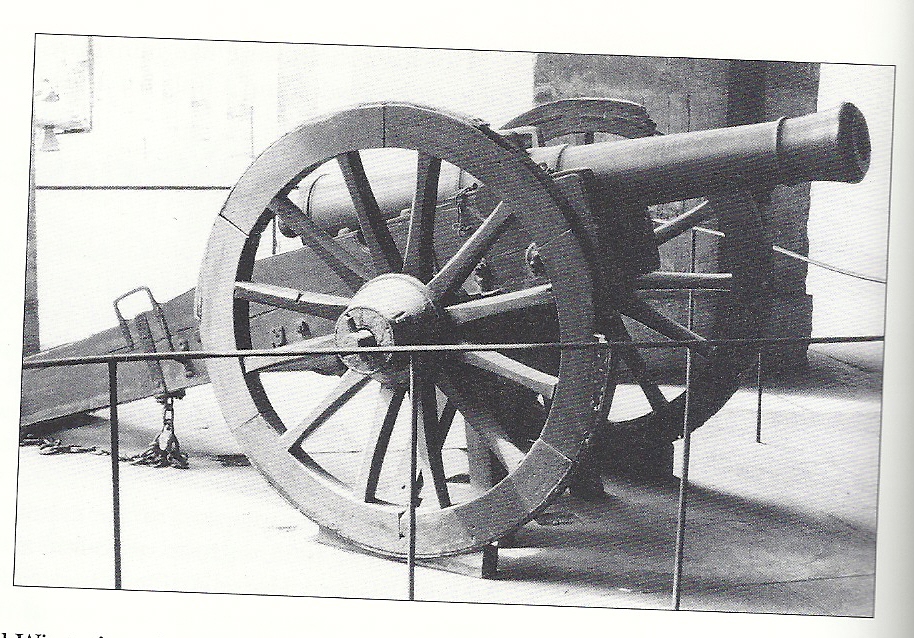

The 4-pdr

Not easy to get right. Easy for me because I had lots of old Battle Honours models to start with, and plenty of wheels of the size I wanted – but these aren’t easily obtainable these days. The only model of the right scale out there that I know of is Blue Moon. But this is let down by wheels that are too small – and the bigger wheels are in important part of the look of French artillery.

The 8-pdr

Much easier, though I cobbled mine together from bits and I did not buy any of the current models. But both Blue Moon and AB look fine – but these will look best beside models in the same stable, though.

The 12-pdr

The BM carriage is too much too long, based on reviews I have read. The AB one is the right size, and nicely detailed, but the trail doesn’t look quite right in my view. I have two of the ABs and three cobbled together models based on the Blue Moon French Howitzer carriage (!).

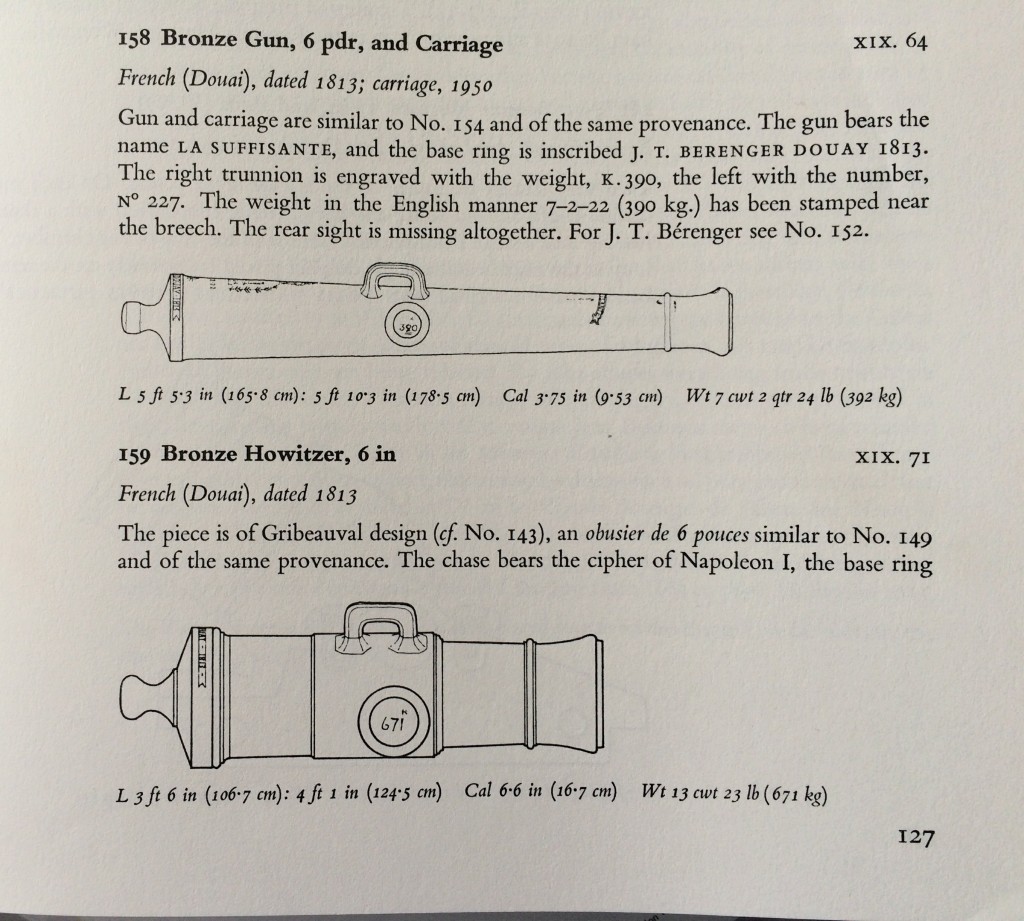

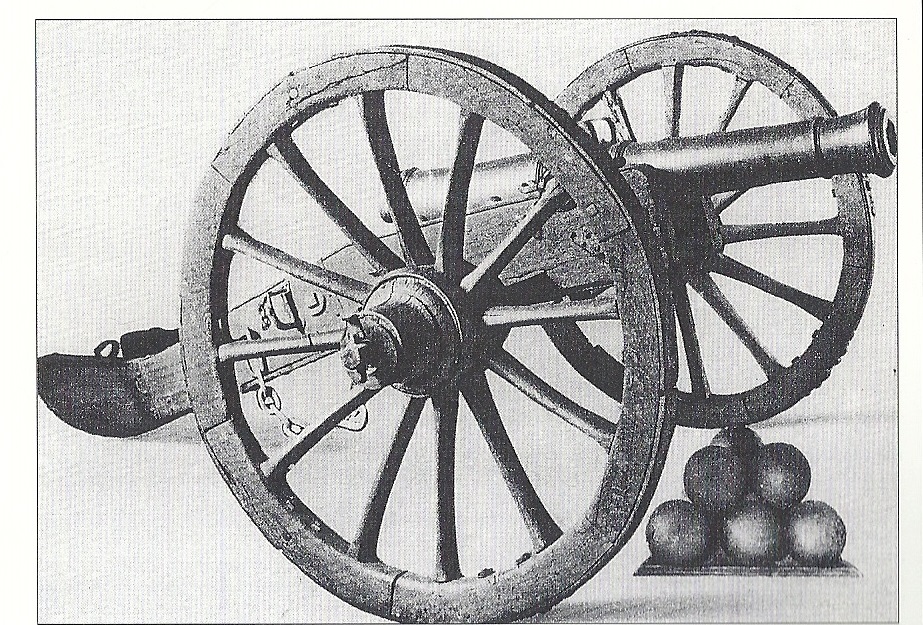

The 6-pdr

The Blue Moon model is essentially sound, but has some errors. The barrel needs to be smoothed; you need a new and higher elevating plate from card. The AB model is nice but based on the 8-pdr carriage, which might be accurate for a few, late weapons, but not for most of the era. The barrel also needs to be smoothed. Also on my old AB models the wheel track was much too wide and had to be cut down. This may have been corrected in current models. This is the main artillery piece for my armies, so I needed lots. I made up six from Blue Moon, to go with my 3 old AB ones, and three more I made up from old Battle Honours Prussian pieces.

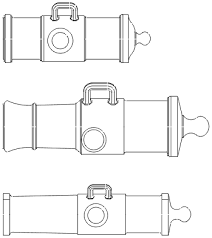

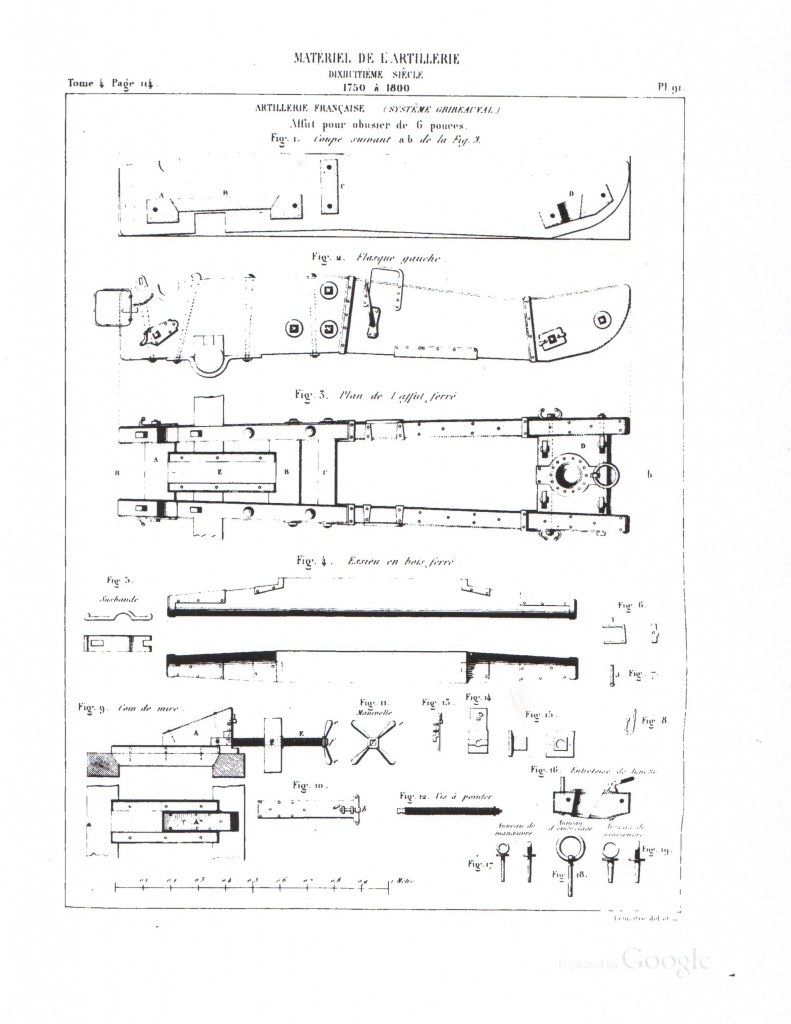

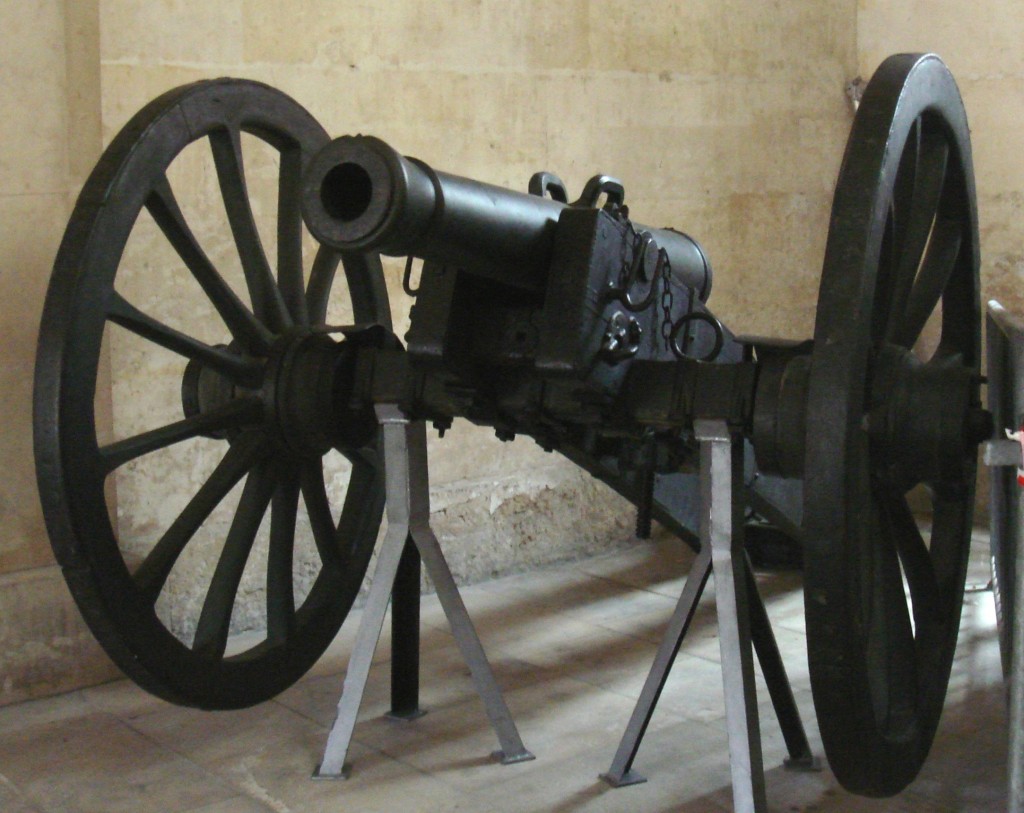

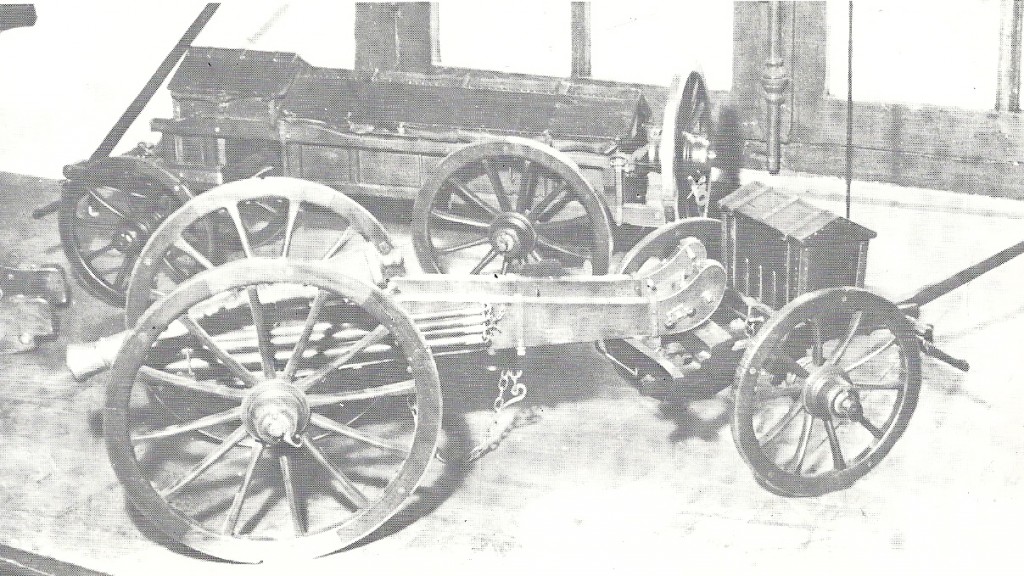

The 6 pouce howitzer

By this I mean the classic French “6 inch” short-barrelled howitzer that is the subject of most illustrations, often described as “Gribeauval”, but which was probably not all that much used in fact. None of the 15mm models I have seen get this right. The carriage for the Blue Moon model is vastly oversized (I used it for the 12-pdr, and it was a bit too big even for that!). The AB model is of generally the right proportions, but looks a bit weedy. And the latest model (mine are old ones) might not even be right based on their illustration. I used a BM barrel on the AB carriage, but still wasn’t too happy!

The 10-pdr howitzer

This is another “6 inch” howitzer, and used in the heavy batteries, right up to Waterloo. But the only pictures I have seen are of the barrel. It was based on an old Prussian design. In fact the simplest way of producing this is to take the AB Prussian “7-pdr” howitzer, which is probably quite close to what this weapon looked like in the later years with a later-style carriage. You can “Frenchify” this by adding trail handles (bend some fuse wire or even a staple) and cut out the ammunition box retaining struts. To get an earlier look I put the AB Prussian barrel on the AB French howitzer carriage.

The 24-pdr howitzer

This was the main howitzer in use by the French, and also, confusingly, usually referred to as “6 inch”. There are no 15mm models of this anywhere that I know of. The closest model is the Blue Moon Prussian howitzer. But the French barrel was slightly longer, and the trunnions further back, so that the barrel projected more from the front. I opted to make my own barrel, but this looked too heavy, and was bit more than my clumsy fingers should have taken on. The Prussian model needs an elevating plate (easy to make from card) and its trunnion recesses are too deep (I filled them with plasticine) – these are applicable to using it in Prussian mode too. Also you may want to Frenchify it – which I chose to do on my 3 models. If you are making your own barrel you can also use the Blue Moon French 6-pdr carriage (or the Prussian 6-pdr come to that).

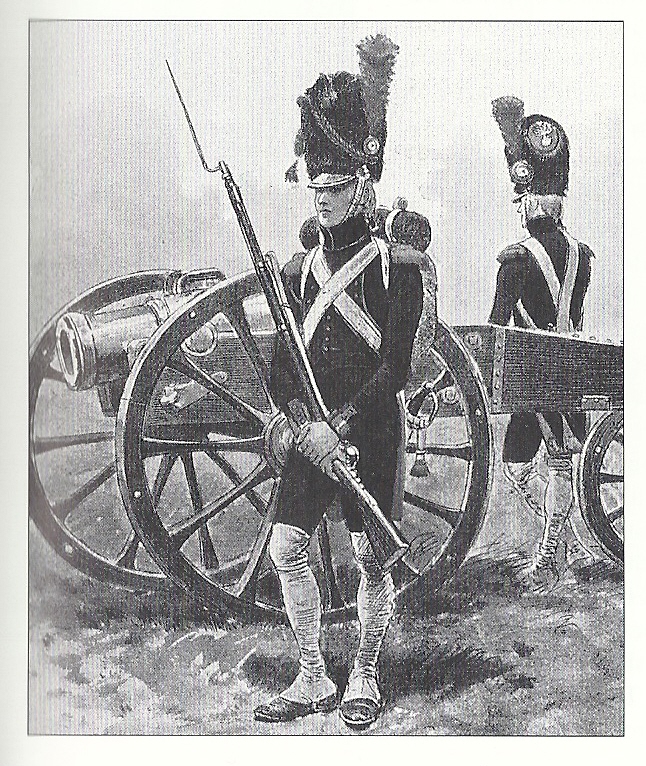

Now a few words about the finishing. I decided to reuse my existing crews. These were Battle Honours foot crews and Old Glory horse crews for the 1809 period, and AB Guard foot crews. I decided not to use my Battle Honours Guard horse crews – they are too small and not impressive enough, or my BH standard horse crews, as these are bit dull. The BH foot crews are bit underscale for the job, though, and this is a bit noticeable if you get the correct 1:100 scale wheels. Still, I use them to make up the numbers.

The Old Glory figures are fine for both scale and appearance – though the gun models that come with them are not particularly useful if you want them to look right (though mine provided carriages for my 8-pdrs and wheels for the 4-pdrs! These were from an old pack, though, and I don’t know whether this would work nowadays).

I don’t particularly like the AB Foot Guard figures either, though they were fine for size and detailing. There is no officer and the pose of figure carrying a n ammunition round looks laughable (casually holding a 12-pdr round as if it was a tube of Pringles), and they are mostly wearing backpacks. Another problem is that I had painted them in too bright a shade of blue (Army Painter spray colour with dark Quickshade). I tried calming this down with washes of dark blue-grey, and then touching up – but this wasn’t altogether successful.

These figures needed reinforcements. I had some Fantassin/Warmodelling crew figures lying around unpainted (bought in Fantassin days). I have been very critical of this range’s artillery pieces, but these figures are perfectly respectable. They are depicted in greatcoats and backpacks, which covers up some uniform details and makes them quite generic – they can double as line artillery or marine gunners. I painted the shakos appropriate to later uniforms.

I supplemented these with later era Blue Moon crews. These are nice figures, depicted with shako covers, tunics and without backpacks. I painted some as line and some as naval gunners (there were some of these at Waterloo, apparently) – though you’d be hard pressed to tell the difference (the naval gunners have red collars).

I am still playing with painting methods. I undercoat with specialist metal undercoat from a DIY store. This comes in a lifetime-sized tin, but the only one I could lay my hand on was water-based and white. A mistake. Diluted paint (it’s much too thick to go on direct) leaves you with issues of surface tension and coverage (not so good as filling the holes). White undercoat is not a particularly good choice for relatively quick-painted 15mm figures. I gave the figures a first thin coat of raw umber after the undercoat, followed by several coats of a blue mix. In another experiment: I created this mix from ultramarine and raw umber (I use artists colours), instead of my usual Prussian blue base. But this needed lots of coats before it started to look right. I tried to highlight with the brighter ultramarine, but the effect was hardly noticeable. The overall effect was rather nice though (incomparably better than Army Painter Navy Blue plus dark Quickshade!), but not as quick as I wanted! Even if it doesn’t come out in my pictures. I did not feel the need for Quickshade, so just did a raw umber wash on the faces.

The bases were new. I need smaller sizes these days. The standard is 30mm square, with 25mm (wide) by 30mm for light guns, and 30mm (wide) by 35mm for the heavies. Two figures populate the bases, except for the heavies, which have three. These aren’t eye-candy. The position of the figures is not realistic. It is all dictated by the needs of games played on a small table. I am also avoiding the thick MDF (or mounting board) bases that are so popular – they do frame the figures nicely. But I feel that height is my enemy on the table, especially since I am forced into using miniaturised terrain. And I already have magnetic strip on the bottom. So I used 300gsm artist’s paper. That’s thick for paper but thin for a base, especially a larger one with a greater risk of warping. Never mind. I have magnetised bases and I store on steel paper, which should stop the warping.

I use a home-made gloop, consisting of sand, artist’s gesso and paint (I used a dark burnt umber this time – I have used raw umber before). I apply this with a sculpting tool after gluing the figures to the base. After touching up with burnt umber paint, I covered the bases with a combination of flock and static grass. I’m not expert with the static grass, which comes out a bit matted in my hands. The flock represents the flattened areas – and only in very small areas is the base of burnt umber left exposed. They haven’t set up in a Japanese garden amongst decorative tufts and rock features. To unify the flock and static grass I give it all a wash of yellow green (using ink and flow enhancer rather than water as a base). I then give a bit of a dry brush with a white/yellow ochre mix. The overall effect is textured and the figure bases are nicely covered up, and the colour doesn’t jar with the table covering. In my earlier batch of bases for my Prussians the overall effect was too dark, which made my dark figures look even duller. So I used a brighter colour of static grass, more yellow in the wash, and was rather heavier (and less dry) with the dry brushing. This looks much better, and I will have to reverse engineer my Prussians somehow. But I don’t think I’d recommend this approach particularly – I think you can get nicer looking results than this.

And now my thoughts turn to my next project. Prussians probably. I have it in mind to do a similar article (or articles) on Prussian artillery, and one on limbers too. But I need more Prussian landwehr!