This book attracted my attention recently – and I’m very glad I bought it. It offers insights into a neglected aspect of WW2 warfare and the use of artillery by the British (and Commonwealth) Army. It’s not a long book, and the core of it, Lyell Munro’s memoir, is padded out with other material supplied by his family, including a general background to the history of the Air Observation Post (AOP) in British forces. Alongside the interesting details of battlefield tactics there is a rather charming personal story, told in the good-humoured style so typical of British accounts of the period. This includes his own commentary on Allied strategy in Northwest Europe (he was not involved in other campaigns). Extracts of letters to his future wife are included, and complete letters of hers to him – they met when she was a nurse, but she moved on to be a Wren. This offers an insight to wartime life and love outside the world of cinematic portrayal.

The AOP role developed alongside the rivalry between the Army and the RAF. At the start of the war the RAF had a complete monopoly of military flight. They had developed an army liaison role, using Lysander aircraft for AOP and other duties, including bombing. The Lysander proved to be an unsuitable aircraft for the AOP role – it was too big and heavy, and too fast (i.e. an airman’s idea of what was needed). Besides, RAF crew did not make good artillery observers. Casualties in these squadrons in France in 1940 were very heavy (118 out of 175 aircraft lost), and the RAF gave up on the idea. The Army, and the artillery, did not. They insisted that if you put an artilleryman in a suitable aircraft, it could be of real value. The aircraft would have to be slow and and agile, with an upper wing so that ground visibility was good (which ruled out the Miles Magister – one candidate). It needed to be able to land in small fields close to the front. The slowness was mainly for the benefit of observation, especially of fall of shot. It also, a bit counterintuitively, reduced vulnerability to enemy fighters. The tactic was to get out of the way and hide in the landscape, even landing if need be. Losses were surprisingly light. Munro’s squadron lost two pilots in the air (at least from June to August 1944 in and around Normandy). One was hit by the fire of the battery he was supporting, the other hit an electricity cable. Munro was acutely aware that his chances of survival were much better than that of an infantry officer. I was surprised that no aircraft were lost to ground fire in his squadron. Flying low and slow they were surely vulnerable. Of course they would try to stay well away from any flak units spotted, especially the feared 20mm quads. Infantry may have feared giving their position away. This is a quote from a Tiger tank commander:

That damned English crow is hanging in the sky again. Doesn’t he know there’s a war on? He’s got a nerve, flying in curves and circles over the front like that! A machine gun could easily bring him down. But nothing stirs in our front line. The infantryman there knows that the slightest sign of life will bring down the shells of the enemy – and they will be bang on target. Throughout the intense heat of the July afternoon our infantry lie motionless in the ground, following with their eyes every movement in the sky above.

Ernst Streng – quoted in “Hill 112” by Major JJ Howe MC

The plane that Streng is referring to may well be Munro’s – the day corresponds to the one when he describes a contest with a lone German Tiger. Incidentally he found that 25 pdrs weren’t enough to deal with it, but it did shift when coming under fire from a 4.5in medium gun he managed to bring in. That forced it to take cover in a village, where it was later abandoned.

The AOP squadrons were flown by pilots from the artillery, like Munro, but maintained by RAF crews, and were technically RAF squadrons. They operated from ad-hoc bases very close to the front line. When not in the AOP role they often ferried around army officers, or flew them over operational areas. Later in the war they also carried out successful photo reconnaissance. The pilot was the principal observer for artillery fire, but they took up an additional crewman (volunteers from the ground staff) to be an extra pair of eyes, especially for enemy aircraft – which remained present through the war – including Me-262 jets later on. Munro describes an encounter with an Fw-190 that had shot down a Typhoon – but didn’t spot him.

The AOP role was considered to be a big success. The Americans also adopted AOPs, using aircraft such as the Stinson L-5 Sentinel (the only purpose-designed AOP – an earlier version of which was the first choice for the British AOP – but the Auster could be produced locally) or Piper L-4 Cub. The Germans may have had a suitable aircraft in the Fieseler Fi-156 Storch, though this was notably bigger and heavier than the Allied aircraft. The write-ups say it was used for artillery observation, but I haven’t seen this mentioned in specific battle accounts. It could be that the Germans suffered from inter-service rivalry too. I suspect the Storch was used mainly as officers’ transport and scouting rather than AOP.

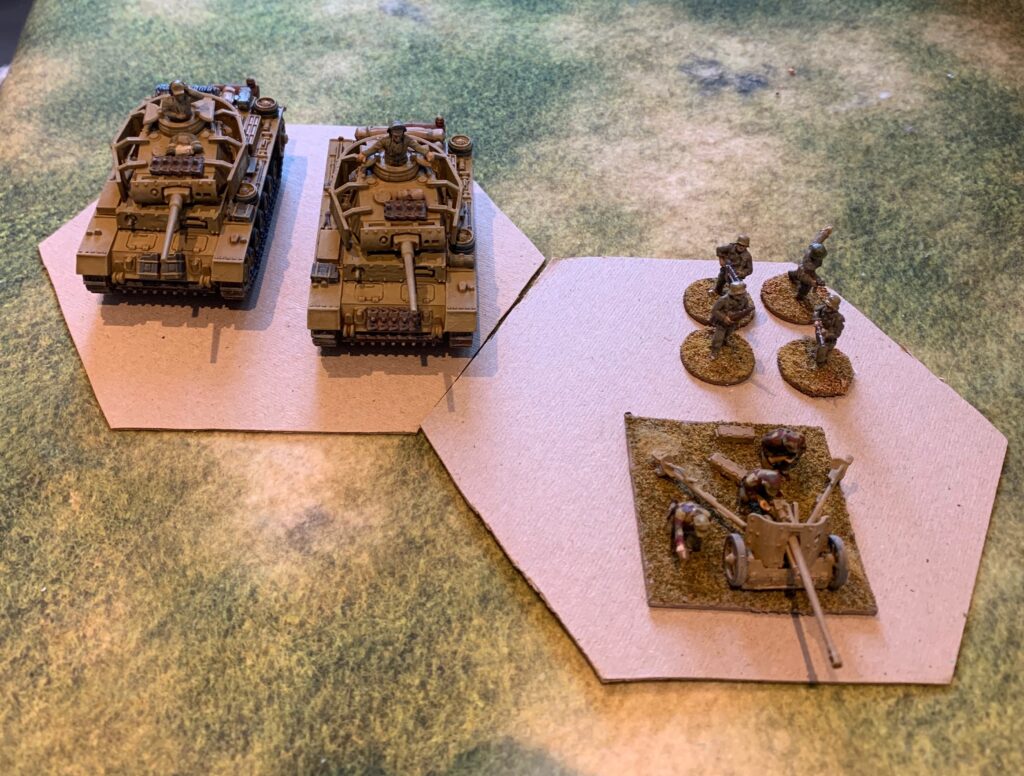

How about AOP in wargames? Many rules do provide for them (e.g. Battlegroup and Rapid Fire!). My sense is that AOPs tended not to be used in the thick of the sort of action we like to war-game – when the battlefield would be quite a dangerous place for a little aircraft – but much more during static situations, or lulls, when artillery was being used to pick off enemy positions. They were also used off-table in a counter battery role. Munro mentions that they were used to try and find mortars – but that German mortars were nearly impossible to spot when firing. They would try to guess where they were and direct a general bombardment in that area, to suppress as much as to destroy.

How about AOP for my 1943 project? The Austers were certainly in use in Tunisia and onwards by the British. This is presumably where tactics were refined before D-Day in Europe. The US Navy attempted to use AOPs launched from ships in the invasion of Sicily – but apparently this was a disaster and losses were very heavy. These would have been big and clumsy floatplanes, fine for observing gunnery in naval battles, but lacking the agility to stay out of trouble over land. There were no Austers at Salerno – but I guess appropriate airfields were lacking and it was too long a flight from Sicily, even if they could find smaller fields to use. Apparently an Auster was used to scout out German positions on Longstop Hill – but I don’t think they were used in the assault.

I have a soft spot for the Auster. My first ever aeroplane flight was in one, in Somerset when I must have been about 10 or 11. This was a treat while we are on holiday. I don’t remember too much about it. I’m sure I was told it was an “Auster 8” – but this does not correspond to any model that I can find. But the shape fits my memory – just about big enough to take my Dad, my brother and me, in addition to the pilot. My Mum wasn’t so keen.

I would like to do a 1/72 model of an Auster in 1943 Med theatre colours. I certainly don’ want to do a Lysander instead, as some wargamers seem to. However there’s a problem about finding a mode. AZ Model produced one as recently as 2016 (in Czech colours but no matter), which is also the right model – a Mark III. But they only seem to do very small production runs and there don’t seem to be any around second-hand. Other than that there is the Airfix Auster Antarctic. This is an early Airfix model, but was produced in large numbers over time, so they do turn up on the second-hand market, although sometimes for crazy prices. This is of a later, post-war mark though (and Airfix did do an AOP version, but one appropriate to Korea not WW2), which is moulded in bright yellow plastic and has optional floats or skis. However the undercarriage, cabin and engine are all different, so it would entail some conversion. The best strategy may be to wait for AZ to reissue.